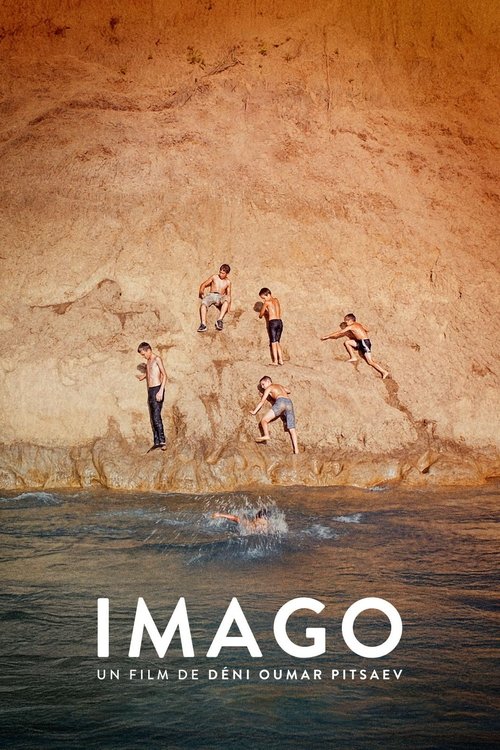

We invite you to meet Déni Oumar Pitsaev, director of Imago, winner of the French Touch Jury Prize and the Golden Eye for Best Documentary at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival, which opens in theaters this Wednesday. Interview conducted by Shiva Fouladi following the screening of Critics’ Week at the Cinémathèque Française.

Shiva Fouladi [S.F.] Thank you very much for agreeing to this interview. You were in Cannes competing at Critics’ Week with Imago, which is your first feature-length documentary, and your film was a great success, winning the French Touch Jury Prize at Critics’ Week and also the Golden Eye Award at the Cannes Film Festival, which is the prize for best documentary film of the entire festival. Congratulations.

Déni Oumar Pitsaev [D.O.P.] Thank you.

[S.F.] Before we start talking about the film, could you introduce yourself and tell us a little about your background, your studies, and what you’ve done previously in cinema? Have you made any short films or anything else?

[D.O.P.] I attended a film school in Belgium called INSAS. It’s a very reputable film school in Brussels, and I was in the directing department. I made two short films, a documentary and a hybrid between fiction and documentary. Imago is my first feature-length documentary, and I’m currently working on a feature-length fiction film.

[S.F.] Why did you choose this subject? Your film is about yourself, the main character who returns to his family after living in Europe for several years. You come from Georgia, a border region between Georgia and Chechnya, and throughout the film it’s about meeting your family and the desire to find your roots. What led you to make this film?

[D.O.P.] Actually, it’s not really a return because I’m not from Georgia. It’s an enclave in Georgia, a Chechen enclave on the border with Chechnya. I come from the other side of the mountain, from the real Chechnya, which is now in Russia. Since I no longer have the right to return to Chechnya—it’s very complicated because Chechnya is part of the Russian Federation, it’s still a colony— my mother gave me some land on the other side of the border, in Georgia, in Pankissi, in this region populated by Chechens, so that I would have something tangible, a kind of home base so that I wouldn’t lose my roots. That was my mother’s wish. It all started with this gift she gave me: “There you go, now you have some land, you have something tangible, something real. You can have a real connection with this place, you have the right to build a house there and you’ll be among your own people. ” That’s how this adventure began. At first, I didn’t think at all about making a film on this subject, but little by little it became a possibility when my father told me he could come and help me. In that case, this land could be a meeting place between the two sides of my family, a kind of land of peace.

[S.F.] When I watched the film, the most important question I asked myself was: to what extent is the film a snapshot of reality, i.e., do you film scenes that occur naturally in front of your cameras, or are the scenes we see scripted? And what about the dialogues?

[D.O.P.] The film is a co-production between France and Belgium. For all French funding, you have to write extensive dossiers and create treatments, scripts based on reality that doesn’t yet exist. So the film was very scripted, but not word for word, not every line of dialogue the characters would say, especially since I had no idea how they would react. My mother, for example, did not appear in the treatments written before filming: she did not want to be filmed or come to Pankissi for the film. My father, whom I did not know very well, I did not know how he would be. In reality, he talks a lot and was very comfortable. All of that was just ideas or projections I might have had; the reality was very different. In terms of staging, there is no written dialogue in the film. Everything people say, they say naturally. The only person who can say they’re acting a little is me. Since I’m the character but also the director, I can direct the scene from the inside. When I’m with my father or my mother, I’m the one who steers the conversation towards what we’re going to talk about. They don’t know what we’re going to discuss; I’m the one who brings up the topics. But since it’s not written, everything they say is said naturally in one take. There are no scenes acted out by anyone and no scenes redone because I wasn’t satisfied. Everything is truly embodied by reality. For example, the scenes with the women around the table talking about freedom and money: we shot another scene with them that was better filmed and better framed, but it wasn’t natural, it wasn’t the same. I preferred the very first scene, which was a bit chaotic in terms of staging and camera placement, with everyone talking at once, but it was much stronger emotionally and very sincere. I took the things that weren’t aesthetically perfect but were perfect in an emotional sense because they were true.

[S.F.] Did you shoot a lot of rushes? What was the editing process like? Did you spend a lot of time on it?

[D.O.P.] For some people it might be a lot, for others it’s very little. I thought it was fine. I think we shot around 80 hours of footage, but I could be wrong, I don’t have the exact figures to be 100% sure. I know people who shoot over 200 hours. We worked on the editing for a long time, and it took us seven months to edit the footage. There were two editors who did two jobs, which is why it was slower.

[S.F.] In almost every scene, you are present in front of (and behind) the camera. Was it difficult to manage both jobs at the same time, or did you not want to hire an actor to take your place? Did you think it could have been easier? Was it very difficult to shoot this way?

[D.O.P.] It would be strange for me to hire an actor for a very personal documentary that embodies me. It wasn’t easy; it was my first experience like this. I hired a personal assistant director for the staging, who is also a director. He was behind a small monitor, and that helped me enormously. As I said earlier, I also directed the scenes from the inside, which wasn’t always easy, but we had a system: we would shoot a scene during the day and the next morning we would watch everything together with the technical team—the director of photography, sound engineer, assistant, and me—to see what worked, what didn’t, and how to improve things for the next scenes. It was complicated at first, but then we got into a routine. We directed right up to the editing room: we also made the artistic decisions.

[S.F.] I saw in the credits that you have a co-writer. Who is this person and how did you work together to develop the script?

[D.O.P.] It’s Mathilde Trichet. She’s not a co-writer but a co-author with whom I wrote the project. She didn’t know the region at all, but she came with me once to scout locations, a short trip. Since it’s a documentary, it’s not really a script with all the characters and dialogue, just projections. It was to help me transcribe my ideas, facilitate the French language, write the files, and think together about the dramatic arc of the film. Even though it’s a documentary, it’s still storytelling; the rules are the same as for fiction.

[S.F.] Do you have any cinematic references, filmmakers whose imagery and style have inspired you? One might think, for example, of Kiarostami or Nuri Bilge Ceylan, who filmed in roughly the same region, in neighboring countries, and above all there is the question of the relationship between man and landscape, as we see in your film.

[D.O.P.] Those are good references. My reference was someone further away from this region but also in a mountainous area: the landscapes of Galicia in Spain. It was the Franco-Spanish director Olivier Laxe with his film Fire Will Come. It’s the story of a character returning to his native village in Galicia. It’s a very powerful film, and the imagery is too. It was an aesthetic reference for the film, even if I ended up straying from it a little. It was a reference in the dossier.

[S.F.] What you say is very interesting because Olivier Laxe was at Cannes with his new film. Did you see his film?

[D.O.P.] Yes, I saw the film.

[S.F.] And what did you think of it?

[D.O.P.] It’s very different from the other film. It’s a real physical experience for the viewer, a real journey.

[S.F.] When did you decide to divide the film into two parts, while you were writing the script or later during editing? In the first part, there’s more of a matriarchal atmosphere, we see a lot of women in your family, and your very good relationship with your mother. The second part, on the contrary, consists of a dialogue with your father, shot in the form of a walk in the forest. How did you make the choice to have these two parts one after the other?

[D.O.P.] The parts in the forest were very important to me. I knew before shooting that this would be one of the key parts of the film. When it was shot, I was convinced that the structure of the film was designed to lead up to this part with the father, which we are not prepared to perceive. The narration of the film is quite gentle until we arrive in the forest; that’s where it culminates towards the end and not in the middle as usual. This atypical narrative is designed to thwart the viewer’s expectations: the first parts show my arrival, the discovery of the place, and we might think that this is what the film will be like; after the mother arrives, it changes, it becomes more intimate; with the father, it changes again, we almost become spectators. This scene lasts about twenty minutes, maybe more, in the forest, and we don’t let the viewer leave either to the right or to the left; we keep them hooked until the end. It was also a desire for physical performance.

[S.F.] There are mise en abyme moments in the film, for example in the scene in the forest where at the end you say that we’re going to end up with the fact that you want to be free. It’s a nod to the viewer that everything we see is a film, planned, with dialogues, etc. Was it something you thought of, to have these little moments of mise en abyme?

[D.O.P.] It wasn’t planned when we were writing, but it came about more during editing. There are several scenes in the film where the mother looks at the camera, reminding us that there is a camera; she is with the young people on the soccer field who are looking at a camera that is not filming. Each time, it is a reminder to stay aware that this is a film being made before our eyes. It’s a performative film: we don’t forget that it’s a film, but it’s also real. It was important to remember that. During test screenings during editing, people said that it was so well written, every dialogue, every scene, and we replied that nothing was written, it’s real. During editing, we damaged the film a little so that it wouldn’t be too smooth, too perfect, so that we would remember every time that what we were watching was true, real, happening before our eyes, that we were witnesses, that we were participating, and that I was offering this intimacy to the audience to share, so that they could be with me at that moment. It wasn’t planned, but we kept all these little reminders so that we would be aware that we are watching a film being made, that we don’t know where it’s going, that it may not be perfect, but that what matters is the emotion. In the second part, like the scene with the father, it’s the film that starts looking at us, the viewers.

[S.F.] Fundamentally, the film is about the status of women, particularly in the scene where we see women talking about their circumstances, about the freedom they wanted but didn’t have, but above all it’s about exile, about the situation of someone who has immigrated, who returns, about uprooting, about the search for roots. For you, what does the film say about exile?

[D.O.P.] I believe there is no way back. I don’t know if that’s sad or not, but you have to accept it. I wanted to come to this place and make this film also to say goodbye better; it’s not a return for me. It’s a return to say goodbye, move on, and embrace a broader life that offers so much more. There are many subjects in life that go beyond my region. For me, it was important to see that it’s not just a return because you can’t return to a country that doesn’t exist. The return was to childhood, where everything is beautiful, innocent, without constraints, with the freedom of a child. There is nothing more universal than being a child: a child from any country understands each other better than adults. I wanted to return to childhood, and when I returned to this region, I realized that I couldn’t go back, that I could no longer return to Chechnya as I imagined it, dreamed it, or remembered it. You have to accept reality as it is. If you leave a place, it’s over. You still have ties, but it’s not the same. You’re kind of between two worlds, and you never really feel like you belong anywhere forever. You can adapt better, but you’ll never really feel like you belong. It’s a bit sad, but it’s up to us to create a new world, to find our place in exile or within ourselves. It can be even more tragic, like for the young boy, a friend I talk about in the book, who is exiled or a stranger in his own country, in his own region. That’s even harder. At the same time, it’s a very gentle goodbye, full of love. It’s this desire to be an individual but also to belong to a group larger than one’s individuality. It’s not the desire to cut ties or say I want to be free and independent. At the same time, I am attached to something, a clan, a community larger than myself. It’s something I really like here, but I don’t want to live only in that, nor in an almost sterile individualism. It’s a utopia to try to combine the two, to take the best of both sides to be more fulfilled and happy.

[S.F.] How did you find the Cannes experience?

[D.O.P.] At the time, I didn’t realize what was happening. I was very happy, but at the same time it was adrenaline-fueled, there was so much going on, it was intense. I was frustrated that I didn’t have time to see all the films I wanted to see. I was both a spectator and a participant with the film. I was the first to be surprised to be selected for Critics’ Week in competition with a documentary. It wasn’t at all the path I had imagined for the film, so I was a little stunned by everything that happened. Afterwards, when I got home, I got sick, I had Covid, I spent two weeks in bed and I didn’t have time to celebrate and say, “Ah, there you go, I was in Cannes.” Now I’m in Marseille for the Critics’ Week reruns. The day before yesterday I was in Paris at the CNC because the film was being screened there, and today it will be in Marseille. I’m starting to meet the audience, to have a real exchange and not be in a bubble, a kind of apnea.

[S.F.] Did you have time to show the film to the people who participated in it, your mother, your father, and what were their reactions?

[D.O.P.] One of the characters, the young boy who is not named in the film, came to Cannes for the premiere, and my mother came too. She saw the film for the first time in Cannes at the world premiere. She sat next to me, very moved, she cried, she laughed, she was a good audience member. She was very happy about the film, very moved. It was the first time she had seen her ex-husband on screen. I could see her body reacting to the film, she was experiencing it very physically. It was funny and moving.

[S.F.] Did the film have a positive impact on your relationship with your father? Because in the film, at the end, we see that it’s a somewhat conflictual relationship.

[D.O.P.] It’s conflictual, but in the end I make peace with him. He is who he is; there are circumstances in life that influence who we are. I’m not going to change my father today, just as he can’t change me. In the end, it’s not a conflict, but we accept that we are different, that we have very different paths, that we can’t change the past. For me, it was important to name things and talk about them. Dialogue is possible, but we have to leave things as they are, accept that we may not understand each other, but that we remain father and son, and keep that in mind.

[S.F.] The film will be released in France on October 22. Do you expect to reach a wide audience or just film buffs who like documentaries?

[D.O.P.] My distributor, Élisabeth, and I hope it will reach a wide audience. The film is so personal that I was afraid it would remain too personal, but in the end it opens up a lot. It touches a lot of people. It’s broader than I imagined, which reassures me and surprises me. I hope that not only those who love documentary films will come, but also those who love cinema in general, who will share these emotions. We’re quite successful at creating dialogue and listening to each other at a time when we’re becoming increasingly polarized. This film would do viewers good.

[S.F.] Last question: can you tell us a little more about your next project? You mentioned it briefly at the beginning. When will you be shooting? What’s the story about? Is it set in France or elsewhere?

[D.O.P.] I can’t say too much yet, but it’s a film co-produced by France, Austria, and Spain, with three producers. It will be shot in Europe on the island of Gran Canaria, opposite Africa. It’s a very special island. The film will be called Mass Palomas. It’s a film about unconditional love for a place that isn’t meant for that, a kind of seaside resort built in the 1980s, all concrete, artificial, geared towards mass tourism with all-inclusive hotels. In this place, there are two lost characters. In Palomas, the weather is beautiful seven days a week. It’s an artificial bubble. It’s a very different film, not personal this time. I’m the director, it’s a fiction co-written with a screenwriter. I don’t act in it.

[S.F.] Thank you very much.

[D.O.P.] Thank you.

Be First to Comment