Last updated on February 17, 2024

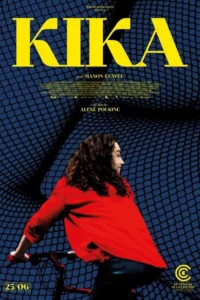

A film by Olivier Assayas

With: Vincent Macaigne, Nora Hamzawi, Micha Lescot, Nine d’Urso, Maud Wyler

April 2020––Lockdown. Etienne, a film director, and his brother Paul, a music journalist, are confined together in their childhood home with their new partners Morgane and Carole. Every room, every object, reminds them of their childhood, and the memories of the absents––their parents, their neighbors… This compels them to measure the distance that separates them from each other and the roots they share, those of their ground zero. As the world around them is becoming increasingly unsettling, unreality, and even a disturbing strangeness, invades their daily gestures and actions.

Our rate: *

Olivier Assayas continues to alternate between intimate French cinema and more mainstream, action-oriented cinema. This time, in what seemed to us to be a very lazy mode, he puts his confinement diary into images, even if he introduces a semblance of fiction by entrusting his role to Vincent Macaigne and that of his brother to Micha Lescot, there’s almost no doubt, if we refer to the respective biographies of the Assayas brothers, that this is cinema en Je. Embarrassed from the outset by Assayas‘s insipid, self-centered letter about the family home, we’re often taken aback by what’s really going on between the four characters, who are forced to cohabit under very privileged conditions during a period of confinement. In addition to the very bourgeois gaze, which is rather uncomfortable because it is far too distant, or even openly distanced, the conversations as a whole very quickly take center stage, in a very talkative cinema, which if it states the intention of reconnecting with nature (as the Impressionists were able to do when they left Paris, a question that visibly haunts Assayas at the time) quickly misses its target, unable to leave an image of nature at rest, unable to let the camera wander on its own or embrace the contemplative gaze that was Assayas’s at the time. Unable, therefore, to play on silences, we have to rely on the performers on the one hand, but also and above all on the voices, and on what emerges from the various speeches. Surprisingly, Vincent Macaigne seems to be striving to copy Olivier Assayas‘s (insipid) timbre and intonation, which he succeeds in doing quite honestly, without convincing us that the idea was a good one. At his side, Micha Lescot plays his brother, again quite honestly, but without convincing us of the virtue of stretching the phrasing to such an extent. Olivier and Michka are called Paul and Etienne in an equally strange way, perhaps in an attempt to blur the boundary between fiction and documentary, or perhaps because they lack the courage and determination to go all the way. The brothers’ quarrels are repeated over and over again, and their annoyances and neuroses are our own. We come to loathe Paul – Olivier Assayas‘ avatar, just as we recently loathed Michel Gondry‘s self-portrait (but here Macaigne saves his character far more than Pierre Ninet did). Alongside them, the two main female characters (Nora Hamzawi, Nine d’Urso) can literally be described as companions, so far from their characters’ development seems to be the priority of this story, which accords them far more of a supporting role. Between the tense conversations between brothers, a few observations slip in about daily life, the confinement itself, and reactions to the management set in place, without flavor, without sparkle, and above all without power or intellectual quality. That said, Assayas has the good taste to insist on what was daily life for many people: in addition to a reconnection with nature, confinement was for many a period of connection, even excessive consumption, thus counterbalancing the distance that the bourgeois condition of this confinement very naturally and shamelessly establishes. Above all, he has the very good taste to bring out other conversations, and to share a few cultivated reflections, some of the works that built him up and still inhabit him (art, painting, musicology, anecdotes, memories and reflections around cinema). It’s not enough to justify Suspended Time place in competition at the Berlinale.

Be First to Comment