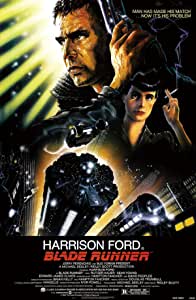

Blade Runner was… Blade Runner 2049 is …

Blade Runner was by RIDLEY SCOTT… Blade Runner 2049 is by DENIS VILLENEUVE…

Blade Runner 2049 is much more like Sicario than the original Blade Runner in essence… The overall impression is that of a calibrated, meticulously crafted narrative that gradually builds in intensity, culminating in a finale where the action builds to a crescendo after a more cerebral opening. First the words, then the pain.

Blade Runner was starring HARRISON FORD … Blade Runner 2049 is starring RYAN GOSLING…

And Ryan Gosling is Drive. Harrison Ford may have been star-struck (and easily identified) with the Han Solo character he plays in the Star Wars saga, but his Rick Deckard character in Blade Runner sounds very different, to say the least, and at no point do we dare draw a parallel between the two compositions. One is a heroic dream machine, a story populated by heroes supported by a resilient people, where humor and fantasy have their place, while the other is resolutely dark, the hero isolated, his struggle essential to his own survival with no real hope for the future, and seriousness the order of the day for two hours. Blade Runner 2049 suffers from too strong an identification with the character of Drive, on the one hand, and on the other, makes the irreparable mistake of reintroducing the character of Rick Deckard as a nerdy, wacky, withdrawn hero. By killing off Scott’s hero, by bringing him closer to his Han Solo character, Villeneuve and Scott commit sacrilege.

Blade Runner was A POLICE FILM OF ANTICIPATION UNDER THE COVER OF AN IMPOSSIBLE LOVE STORY… Blade Runner 2049 is A FILM THAT NO LONGER ANTICIPATES ANYTHING AND IS LITTLE INTERESTED IN THE FEELINGS BETWEEN BEINGS…

Blade Runner‘s narrative has three clear intentions: to develop an impossible love story, to maintain tension and mystery in connection with a police operation, and to deliver an anticipatory vision of society. Blade Runner 2049 takes up some of these anticipatory concepts, modernizes/updates them a little – holograms and flat screens, a dream-producing machine (very unconvincing), and centers its story on a war between androids of different generations.

Blade Runner was MYSTERIOUS from start to finish… Blade Runner 2049 is EMPHASIZED, TINTED WITH EVIDENCE…

Ridley Scott had the good taste to invite the viewer to see Blade Runner several times over, in order to unravel the mysteries, the numerous shortcuts – almost ellipses – that give the first viewing an impression of maintained secrets, of narrative mystery. It also had the good taste to constantly cast doubt on the truth and linearity of the story. Emotions are omnipresent, even in the tears of the most torturous androids: their reversals of thought, their existential doubts, reflect on the viewer’s possible interpretation. There are several possible interpretations of the film’s progress: an optimistic vision of the predominantly bleak plot can be heard if we notice those few moments when feelings – awareness of the other’s affect, love – are introduced when we no longer expect them. Villeneuve, for his part, makes the open choice of offering a film that could appeal to both. For the discerning viewer, he doesn’t give away the answers right away, but rather hints at them. 10 minutes later, so as not to lose the popcorn lovers along the way, he backs up what might have been felt, closes the debate, puts everyone on the same path to understanding. What a mistake!

Blade Runner was SINGULAR… Blade Runner 2049 is INDUSTRIAL …

To convince yourself of this, simply compare the two final scenes – without revealing them, of course. Blade Runner‘s final scene opens up an almost infinite field of possibilities, an absolute non-answer to the societal problem, but also to the very possibility of a sequel. The ending is resolutely open-ended, leaving viewers free to imagine the thousand and one possible sequels, which would have been better left undecided… The end of Blade Runner 2049 is not hidden at all; it’s certainly open, but open to a possible sequel with a follow-up to come. Clearly, Villeneuve is saying: wait, it’s not over, there will be a sequel! A saga will be born! Ah, business …

Blade Runner was SLOW … Blade Runner 2049 is SLOW…

The main pitfall has been avoided: the pace of Blade Runner 2049 is progressive, mostly static like the original work, and this is to be applauded, as the times tend to want to make everything more vivid, flashier, more immediate, at the sacrifice of perspective and permanence.

Blade Runner was FASCINATING… Blade Runner 2049 is PER INSTANT INTRIGUING

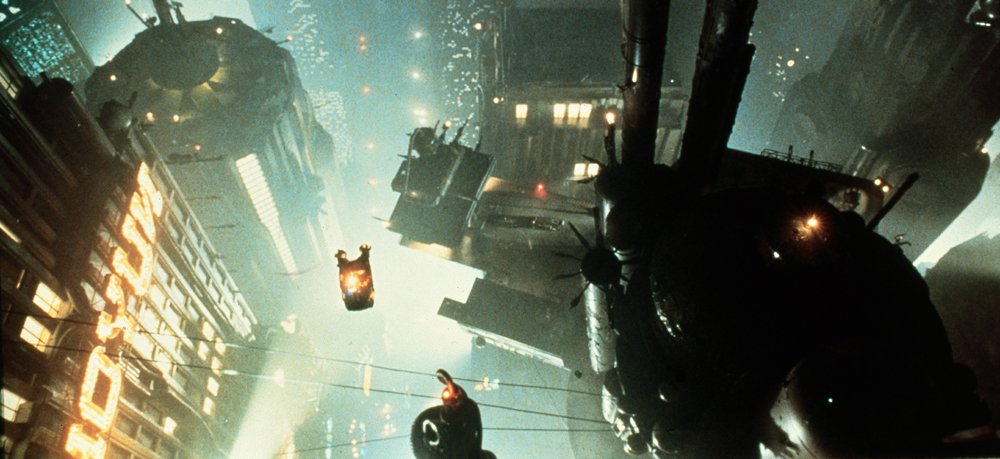

It only takes a few minutes to realize that Blade Runner is taking us to a place we don’t know, to an anticipated setting like no other. We quickly become attached to the story, the character and the atmosphere. Every shot confirms the tightly held line. Our gaze is captivated, our brain analyzes, tracks, observes and is baffled. Blade Runner 2049, on the other hand, is a rehash of the old and tries, without ever succeeding, to reinstate the very special atmosphere that Scott had planted in this Los Angeles of 2019, where the buildings compete in height and majesty, where the neighborhoods swarm at the same time as they become impoverished (Chinatown). Villeneuve’s characters are mostly chilling, and seem to be animated very mechanically, with no intrinsic complexity. They don’t doubt, they move forward with certainty. The story quickly loses its way, ambivalently, in that it gives away far too many points of reference, both spatial and temporal. The story also clumsily tries to play on the nostalgia card, on emotional memory, by calling up extracts from Blade Runner… This has the merit of immediately tempting us to revisit the original work, and arrive at the sad conclusion that the new version certainly suffers from the comparison. A problem of inspiration, of creativity.

Blade Runner was APOCALYPTIC… Blade Runner 2049 is POST-APOCALYPTIC…

Ridley Scott and his team had taken great care to set the story in a clearly apocalyptic atmosphere, where light only has its place in rays. Neon lights are the order of the day in a dark, rainy, smoky night, and relationships between people seem most complicated. Individuals struggle, surviving much more than they live, in a society where the police play an essential role, both protective and repressive. Our main hero has no help but drink to invent a happy life. Villeneuve alternates between a Mad Max-style setting, where radioactivity has made all human life extremely complicated, and desert-like climatic conditions: the muggy, icy atmosphere gives way to extreme heat, and a verdant, resolutely ecologistic, luminous setting, a sign of hope that is ill-timed to underpin the dramatic plot.

Blade Runner was BEAUTIFUL… Blade Runner 2049 is COMMON…

Despite some not uninteresting visual discoveries, the universe proposed by Blade Runner 2049 seems almost familiar (Mad Max like, you might say), when Ridley Scott succeeded in 1982 in transporting us to an unparalleled, mysterious, apocalyptic, stylish elsewhere, questioning humanity and its destructive propensity. He was the first to design cities populated by spaceships and gigantic neon lights, and to explore a more vertical third dimension – a veritable invention when it came to imagining Los Angeles, and one that would later be used in almost all science fiction films (isn’t that right, Mr. Besson?). Every shot in Blade Runner is studied and consistent in quality with its predecessors. The shots in Blade Runner 2049, on the other hand, often seem borrowed, industrialized and bloated. A sense of overload is quickly felt.

Blade Runner was CENTERED ON HUMANITY… Blade Runner 2049 is CENTERED ON ANDROIDS…

Rick Deckard is a human Blade Runner who, in the midst of other humans, hunts down androids that have developed feelings and become dangerous because they can’t be controlled. Ryan Gosling plays a next-generation Blade Runner (android or human, we’ll leave the suspense to you), very cold, in the midst of a predominantly android population, chasing androids whose emotions are not obvious to us… Rick Degard evolves in an environment where distractions still exist between men, whether in bars, strip clubs or street-side restaurants. Ryan Gosling‘s character goes home most of the time to talk to a holographic woman who doesn’t even have materiality. Blade Runner gave us hope that man would triumph over his inventions, but in Blade Runner 2049 the battle is already lost.

Blade Runner was AN INTENSE ATMOSPHERE FILM… Blade Runner 2049 is AN ATMOSPHERE FILM THAT ALLOWS ITSELF TO BREATHE…

Nothing was left to chance in Blade Runner to set the mood. Throughout the film, it’s all about torrential downpours, nocturnal atmospheres and smoke-filled rooms. The interiors and exteriors are all extremely disturbing.

Blade Runner 2049 allows itself small oases where life is good, interiors luxurious and classy … offering a contrast with exteriors where everything is heat, explosion, and radioactivity unwelcome.

Blade Runner was NOVEL IN ITS TAKING … Blade Runner 2049 is an IMITATOR OF BLADE RUNNER’S POV…

Many of Blade Runner‘s shots start with an overhead view, showing a facet of the city, before plunging into its underbelly, into the overcrowded alleyways where our hero wanders as best he can, in an atmosphere that we can only imagine is unbreathable. Villeneuve repeats these plunges without proposing/imposing his own signature. Worse still, the film is released in 3D, which it makes absolutely no use of! It could have been renewed, it could have been dizzying, but Blade Runner 2049‘s 3D is a complete failure.

Blade Runner was SUBTILY RYTHMED BY VANGELIS… Blade Runner 2049 is INTERESTING BECAUSE OF ITS SOUND AMBIANCE…

Synthesizers are probably responsible for some of the most pop and light-hearted sounds there are, but we have to admit that artists such as Vangelis, Tangerine Dream and Bryan Eno have made marvelous use of synth strings to create a very special atmosphere. Michael Mann’s films Blade Runner and, more recently, Drive are perfect examples; if the directors had opted for violins, these films would never, ever have had such an aura. Blade Runner 2049‘s soundtrack is much more mechanical, much more ordinary, but having said that, the ambience is very well crafted, and particularly interesting in that it offers sounds of a disquieting nature, halfway between industrial sounds and musical ambience.

Blade Runner was ahead of its time… Blade Runner 2049 is IN THE CURRENT HOLLYWOODIAN MOVEMENT…

Blade Runner was more than just a futuristic tale: it was a work ahead of its time, inspiring many filmmakers and viewers alike, and opening the door to new imaginary worlds. While there may be a kinship with the atmospheres that John Carpenter infused into his futuristic films, and Ridley Scott has borrowed from them, the form and special effects are so finely crafted as a whole that they mark a clear break with what the film industry could offer elsewhere, even though a few years earlier George Lucas had set the course for large-scale American production, reinventing Hollywood. Villeneuve, on the other hand, seems to us to have entrusted the special effects of his film to the trendy company of the moment, who served him the soup they usually serve. Technically very successful indeed, but artistically worthless.

Blade Runner was A STRONG SCIENCE-FICTION PROPOSAL… Blade Runner 2049 is a NEUTRAL SCIENCE FICTION PROPOSAL…

The magic of K Dick’s science fiction doesn’t work in Blade Runner 2049 when it did in Blade Runner. This is down to the few bits of string used to glue the two stories together, and to the intention to modernize what had already been proposed, without ever asking the question of creating new universes. The science fiction we’re served up seems at best old-fashioned, at worst abracadabulous…

Blade Runner was CULTE … Blade Runner 2049 is ORDINARY…

As you can see, with Blade Runner 2049, the sublime remains at the quayside, and if there’s no sacrilege involved, Denis Villeneuve doesn’t succeed in the mad gamble of inscribing Blade Runner 2049 in the sacred, nor even in prolonging the cerebral pleasure conferred by Scott‘s masterpiece – probably fortuitous given the rest of his filmography.

And so it goes on…

Be First to Comment