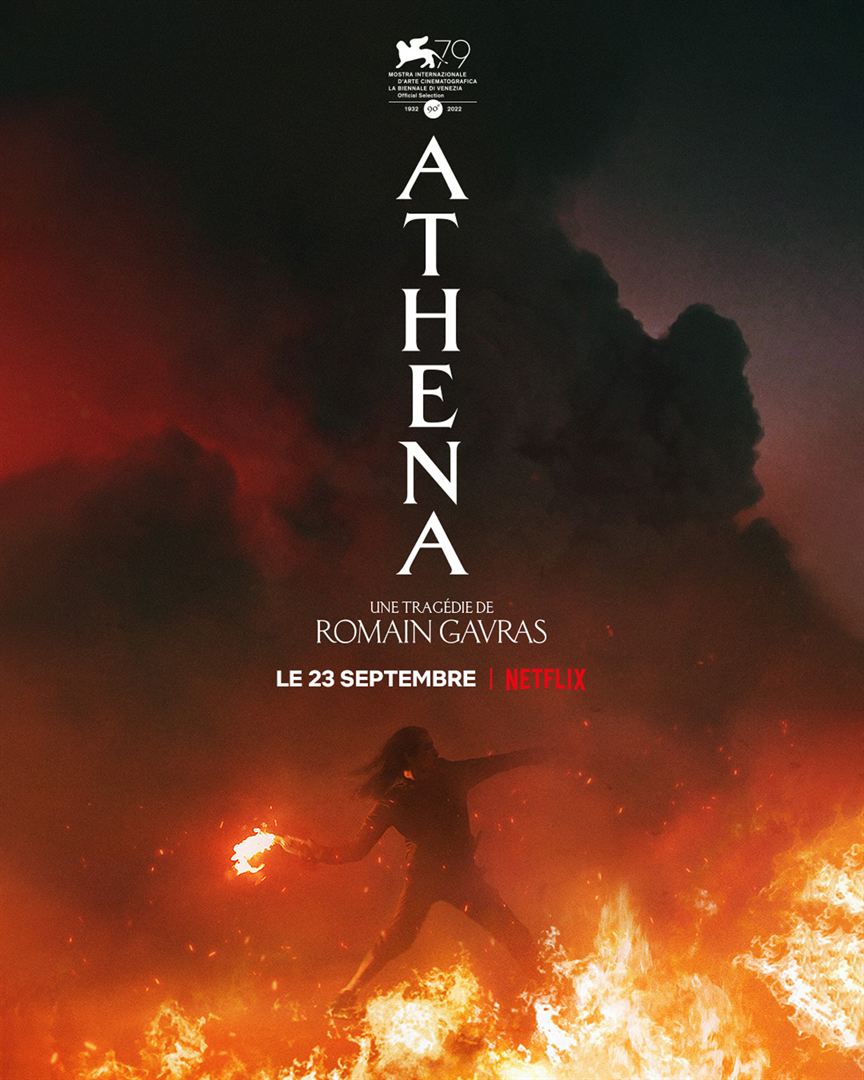

After the death of his younger brother following an alleged altercation with the police, Abdel is called back from the front to find his family torn apart. Caught between his younger brother Karim’s desire for revenge and his older brother Moktar’s criminal actions, he struggles to calm the growing tensions. As the situation escalates, their community Athena becomes a besieged fortress, becoming the scene of tragedies for the family and beyond…

Romain Gavras‘ Athena is one of those few films that make critics want to turn into figure skating judges, and to be satisfied with an evaluation rather than an analysis. On the technical side, Gavras tries to impress us: whether it’s the constantly moving camera, the sequence of shots, the explosive transitions, the constant fireworks, or the choreography, he has little to envy to the amateurs of the style, from Gaspar Noé to Mendes through Nemès. We already knew that, no surprise there. It remained for us to judge the content, the story, the reflection, the psychological depth, but also the form, on the artistic level this time.

Our day will come, under its revolutionary accents, and a bit of a joke, carried a reflection, a look; certainly less refined than that of his father Konstantinos (Costa-Gavras), but not uninteresting. The World is Yours was much more on the side of mischief, or in that of homage to a specific genre, the heist comedy. With Athena, alas, his attempt to bring a modern Greek tragedy to the screen, in our opinion, fails perfectly. On the artistic level, it is difficult to note a gesture, a particular intention. Gavras seems to have put the technique at the service of … the technique to sell. The expressions “to watch oneself being filmed” or “makers” have perhaps never found such a good example. The technical feat, the multiplication of sequence shots that require great coordination, the desire to color the image with a thousand lights, a thousand tensions and crashes, seem to be the main motivations in fine. Everything seems to be driven by this unique intention to show off, even if there is nothing to see, rather than to give to see, to transmit emotions, to enlighten, or on the contrary to open spaces of reflection and emotions, through the intermediary of the technique.

Little helped by a hyper supported dramaturgy, a la Netflix, without any finesse – the Greek tragedy seems here to have little resonance and to have the value of a pretext -, the underlying political look sows the doubt: does Gavras idealize the revolution, does he call it, does he fear it, or does he observe it? Perhaps unknowingly, he is in any case the perfect relay of foreign media that depict France as a hostile territory where civil war has already begun. He even pushes the cursor a little further, by imagining a generalized revolt in the suburbs, a general conflagration. To what end? How does he see it? Is he calling for such a revolt to follow or is he warning against it? In any case, it is difficult to see the very respectable gesture of Our Day Will Come, which, by imagining a rise of anger in an unjustly oppressed population, mocked, without the society being offended by it or even interested in it, carried an obvious message of fraternity, coupled with an interesting psychological look (the history of violence, one might say) On the subject of the rise of violence in the French suburbs, as well as that of police violence and exactions, society is already openly concerned, and many spotlights are already on it.

Gavras can’t take on the role of a whistleblower, nor even of an enlightened expert on the issue, so much so that his Greek tragedy wrapping makes him take shortcuts, so much so that his look reminds us of that of an American tourist frightened by the violence of the images of the riots in France as relayed laconically by CNN, whether he’s passing through Montmartre for the richest or in his couch in the US for the poorest.

After this disturbance, and unfortunately too quickly resolved, the only thing that remains for the spectator is a continuum that the first images, certainly dazzling, or the soundtrack (rather distressing, especially coming from Gavras) had announced too much: The action, only the action, the repetition of the action, and the weariness that, very quickly, invites itself.

Be First to Comment