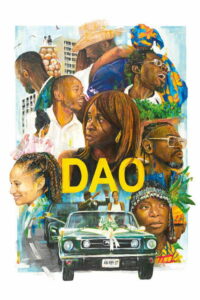

A film by Léonor Serraille

With: Andranic Manet, Pascal Rénéric, Théo Delezenne, Ryad Ferrad, Éva Lallier, Lomane de Dietrich, Mikael-Don Giancarli, Clémence Coullon, Clyde Yeguete, Claire Bodson

Right in the middle of a school inspector’s visit, Ari, a 27-year-old student teacher, collapses. Angry with him for being a failure, his father kicks him out of the house. Emotionally raw, and alone in the city, Ari reluctantly forces himself to rekindle his relationships with old friends. As his memories of the previous months successively ebb and flow, Ari discovers that other people aren’t doing as well as he imagined, and that perhaps he has been sleepwalking through his own life.

Our rate: **(*)

Leonor Serraille returns to an intimate, highly personal and somewhat singular material, despite its universalism, to offer us a strange object. Ari stems from a fascination with the work (and life) of Odilon Redon, and more generally from a keen interest in painting, its effect on the soul and vice versa. Having spent many long minutes repeatedly pondering Caroolus-Duran’s painting L’homme endormi (on show at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille), and its media power, it became clear to the young French director that she wanted to offer us an (unconscious) variation on Montparnasse Bienvenue, this time with a trajectory that avoids all triviality and dares to speak simply about simple things: the difficulty of mourning, the difficulty of feeling rejected, the difficulty of living and confronting the gaze of others, the difficulty of finding one’s path, the difficulty of expressing oneself freely and evoking what’s on one’s heart, without hurting others, just to re-establish a balance, the difficulty of getting back on one’s feet, despite all the dark ideas that can sometimes cross one’s mind when the winds are contrary, the need to build oneself, to find one’s place, to love and be loved. Montparnasse Bienvenue, relied heavily on Sue Lost in Manhattan, so despite Laetitia Dosch‘s sparkle and the energy she brought to her character Paula, in psychological perdition – on the verge of cracking, but who managed to make her misfortune her strength – we couldn’t help but empathize with such a free-spirited character. Leonor Serraille already had a message about existence running through her mind, without, however, sharing Kollek‘s totally disillusioned vision, which fatalistically spared Sue’s fate nothing. On the contrary, Paula refuses fatality, trusts her lucky stars, believes in her chances, in herself, in what others can bring her, in her destiny, in beneficial external events, an attitude conducive to her inner rebound. Kollek plays with this, allowing a glimpse of light at the worst possible moment, only to strike the viewer with a blow at the final verdict, a chop of rare darkness. Serraille firmly refutes this morbid observation, this possibility of an existence in which one dream after another is shattered. She prefers to nurture great faith not in the present, but in the future, regardless of the weight of the past, the obstacles, traumas, impediments and other closed doors. Thus, Redon began to paint his second son – who survived, unlike the first, who died at birth – in color, whereas all his previous paintings were dark. This return to the light, destiny taking its revenge, was Ari‘s subject, and all that remained was to build a character that reflected it, this time no longer borrowing from Laetitia Dosch‘s personality (Paula resembled Leonor Serraille in her background, but not in her character, they told us), but rather reflects something deep-rooted in the director, who has taken up the challenge of speaking from the heart, as a child might, who doesn’t question his image, but simply expresses himself, shares his feelings, needs others, seeks their gaze, and even more than an adult, shows that he needs to be loved, and to love. This is a starting point, and the film opens with a very explicit scene, in very close-ups, showing how important it is for a child, but also for a mother, to show infinite tenderness to each other, but also answering from the outset the question that the viewer would otherwise have been asking throughout the film: why the name Ari? Léonor Serraille admits that it doesn’t matter whether Ari is a boy or a girl: the precise state of mind that the film attempts to translate onto the screen, the slice of life narrated, touches on the universal, and could just as easily concern a man or a woman. The sleeping man, the man who has let his heart leave his body, who has lost his childlike soul, can wake up at any moment. This man will be Andranic Manet, an obvious casting choice, and the exchange we’ll have with him, as well as the result on screen, can only confirm it. Andranic Manet has the characteristic of having within him a range of emotions from the darkest to the brightest, of being able, like a child, to move quickly from a very sad emotion to a joyful one, All it takes is a positive sign, a touch of attention, a connection, and his face lights up, his smile returns, he speaks with confidence and ease when a few minutes earlier he seemed totally absorbed by something else, an embarrassment, a form of shyness somewhere, or a lack of self-confidence – his natural humility also shines through at all times, a feeling we also had when we met Karim Leklou to whom he reciprocated in Le Roman de Jim. In this way, the two of them, drawing on numerous details and references – here too, we invite you to listen to our interviews with Léonor and Andranic – refine the portrait, Léonor Serraille composing with a form of seriousness that Andranic brings, unvarnished, at the opposite end of the spectrum from Laetitia Dosch‘s mask, an apparent frivolity, two possible reactions to the same stimulus, opposites. Ari explores other possibilities, showing anger, liberation and different mental constructs, all the while returning to the way of the cross, the depressive slump, and the importance of others, of chance, the ability to remain dignified even in the descent, not to collapse, never to give up. Ari, in a way, is an introverted version of Paula, rather than an evolution or extension of her, a few years later, and Léonor Serraille, without realizing it, without intending it, delivers us a reverse side of Montparnasse Bienvenue, with an emotional potential that should speak to the greatest number of people.

Be First to Comment