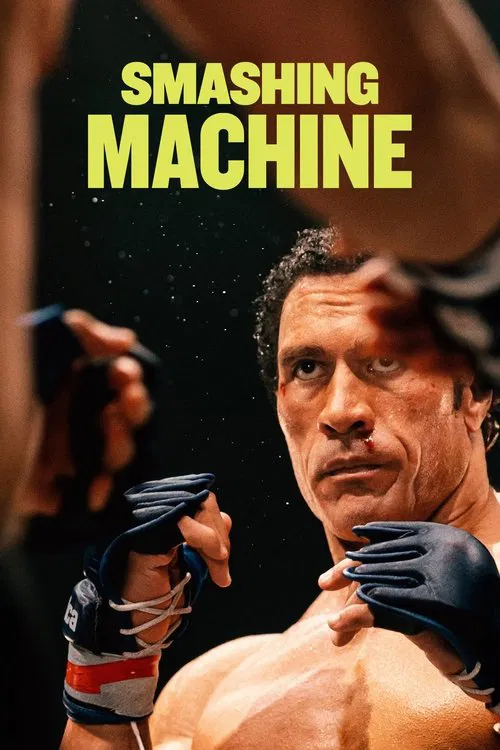

With The Smashing Machine, Benny Safdie delivers a portrait reminiscent of what Ferrara might have offered in the 1990s, or what Aronofsky achieved rather successfully with The Wrestler at the beginning of this century: that of a weary hero, plagued by his demons, who tries to fight against himself, to fight at all, and who struggles to lead a fully successful life. It is a touching portrait that plays on human nature, amplified by the hero. The impulses of life coexist with a death or destruction impulse; the impulses to conquer and surpass oneself contrast with the need for tranquility, gentleness, and the search for affection and simple happiness. The big-hearted hero touches us with his tenderness, but terrifies us with his weaknesses and his failures. Darkness constantly rubs shoulders with light, with a constant shift from one to the other, and the descent into hell looms large, but sporting success tries to make us forget it.

Benny Safdie‘s aesthetic is less flashy than what he has done before (with his brother), in order to strike a more accurate chord. Effective and relatively simple, the drama relies in particular on the performance of Dwayne Johnson, transformed (an Oscar-worthy role!) into Mark Kerr, whose gloves he slips into perfectly. The violent fight scenes are scattered throughout, with only the second half of the film giving them significant screen time, in an approach reminiscent of Rocky and, before that, Raging Bull (the hero who rises again through the sweat of his brow), to better establish the initial theme.

In a way, everyone could identify with Mark Kerr. Safdie himself seems to be a fan of free wrestling, the precursor to MMA, which may be why he doesn’t hesitate to emphasize the violence of certain blows, but also to shorten the fights even more than sports highlights do. Above all, he seeks to modernize the values conveyed by Rocky in his day. Here, the American dream leaves no room for the American nightmare, a gap into which many independent filmmakers, exasperated by the fallacious and reductive nature of fairy tales, have slipped: Safdie opts more for a “both at the same time” position, in which the two go hand in hand, where humans can both win and lose, and where winning is no longer necessarily the ultimate goal. Here, Mark Kerr will not shout “Adrianne, I won!” On the contrary, the hardest battle he fights is not necessarily in the ring, but rather on the domestic front. If he wants to be able to love and live in harmony, he will have to make a choice in order to hope to claim victory.

Despite its limitations (simplicity, weak writing for Emily Blunt‘s role, lack of background or intellectualization, a certain tendency toward repetition rather than depth), The Smashing Machine offers honest entertainment, carried along by jazzy ensemble music that gives way, in the background, to other more rock ‘n’ roll tracks in keeping with the aspirations of the film (Springsteen, Rolling Stones) and its title (The Smashing Machine, reminiscent of The Smashing Pumpkins), which contribute to its good pace. In this respect, it reminds us of Ali Abassi’s highly electric The Apprentice.

Be First to Comment