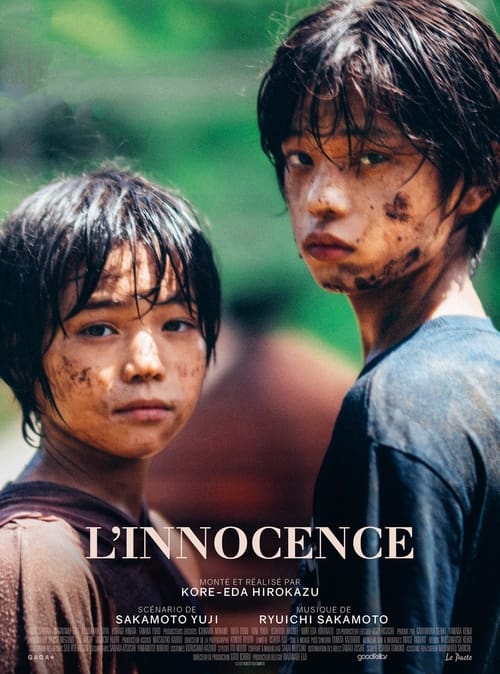

Young Minato’s behavior is becoming increasingly worrying. His mother, who has been raising him alone since the death of her husband, decides to confront the teaching staff at her son’s school. Everything seems to point to Minato’s teacher as being responsible for the boy’s problems. But as the story unfolds through the eyes of the mother, teacher and child, the truth reveals itself to be far more complex and nuanced than anyone had initially anticipated…

Kore-Eda, as productive as ever, continues to spin out a coherent body of work, in which the themes of childhood and family, approached from mostly sociological angles, occupy a predominant place. For a long time, the director was dubbed the “Japanese Truffaut“, precisely because of these obsessions, but also because of his penchant for clear, intelligently romanticized narrative structures. Now, from film to film, he strives to alternate between a linear body of work that would form a whole, but also to allow himself a few detours, attempts here and there, to try out areas or styles that interest him but in which he is not necessarily expected. The Third Murder, for example, with its doistoievskian overtones, is a major departure from his filmography. Both fox and hedgehog, to quote the late Michel Ciment and Isaiah Berlin before him.

With Monster, while there’s no doubting his hedgehog nature when it comes to primary themes, Kore-Eda ventures into territory more alien to his primordial cinema when it comes to secondary themes and form.

For example, he opts for a narrative structure akin to Rashomon (or, more recently, The Last Duel). In the final third, he raises societal issues that are perfectly in tune with our times, aiming for the universal through the prism of the oppressed.

This “literary” ambition, to deliver his story in a willingly fragmented fashion at first, so as to fill in the ellipses little by little, naturally keeps the viewer interested (and alert), who finds himself, as in a detective thriller, in the position of a detective tasked with piecing together the truth (with no connection whatsoever to the director’s film of the same name) from different points of view, known elements and areas of shadow that gradually come to light. It also allows Kore-Eda to hide his game, and not to tackle his real subject head-on, but to introduce it gradually, allowing it to infuse the mind bit by bit, the better to reveal itself and delay its (emotional) effect as long as possible, so that its climax is all the more striking.

Through this imminently precise work, but also insofar as it includes its share of “twists”, Kore-Eda certainly succeeds in constructing a patient, well-crafted scenario that, as is often the case with him, contains its fair share of vertigo. Childhood, the family, the social milieu, unions and break-ups, differences of opinion linked to social condition, are all examined with a fine-tooth comb, as in all good Kore-Eda films. But … The rather well-maintained mystery of the film’s first two-thirds, and the process of delaying a forthcoming revelation, which are of great dramatic interest, also entail their share of risk, even disillusionment, if the expectation – in terms of both form and content – thus created is not perfectly fulfilled.

Instead of confirming or sublimating the mystical aspect that the first two-thirds of the film suggested, the third part of the film is willingly explanatory. What we had, alas, begun to sense, suddenly occupies the entire space of reflection (the screen, the narrative). It’s no longer a matter of questioning, but of answering plots and root causes, and simplifying the potential psychological labyrinth when cause and consequence can’t be separated. Kore-Eda delivers a message that’s simple and limpid, but consequently lacking in depth.

It reveals the other side of the coin, the original fault and its direct consequence. These are the very issues that had already interested other filmmakers, with different sensibilities and approaches (Franco with strength, mastery and rage, Dhont with sincerity, benevolence and big emotional strings). Rather than being brilliant, the effect was, for us, very different from what we had expected. Rather than succeeding in communicating pathos, the relatively mechanical process detached us from it, and the ingenious final scene didn’t allow us to hang on to it. Good to very good in its own right, Monster will remain for us a rather lambda Kore-Eda.

Be First to Comment