Last updated on September 4, 2024

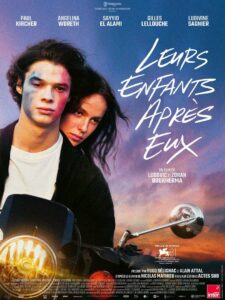

A film by Delphine Coulin , Muriel Coulin

With: Vincent Lindon, Stefan Crepon, Édouard Sulpice, Benjamin Voisin, Sophie Guillemin, Arnaud Rebotini

Pierre, a devoted father in his 50s, raises his two sons alone. When Louis, the youngest, leaves home to attend the Sorbonne in Paris, Fus, slightly older and not as successful academically, becomes more and more secretive. Driven by a fascination for violence, he gets entangled in far-right extremist groups, at the very opposite of his father’s values. Between them, there is love and hate, until tragedy happens.

Our rate 1: **

A French-style social film that tackles a highly topical issue: the country’s extreme right-wing tendencies, the resurgence of fascist (and more generally extremist) ideas, and the radicalization of opinions. So it’s no surprise to find Vincent Lindon in the lead role, as the courageous, loving father of a bereaved family, but overwhelmed by the turn of his son’s teenage crisis (interesting Benjamin Voisin, in particular, for moving from one register to another, from the child who loves his father and family, to the young adult who wants to emancipate himself and assert himself politically, in rebellion against the left-wing ideas his father tried to inculcate in him). Formally, the Coulin sisters opt for sobriety, in a style somewhat reminiscent of that of the Dardennes brothers, to raise social awareness, even if they do allow themselves a few musical accelerations to quicken the pace. The linear narrative focuses on properly introducing the characters, their convictions and the ties that bind them together, seeking to draw a social portrait that we sense is the original breeding ground, with a form of didacticism being introduced for dramatic purposes (the film seeks, clumsily in our view, to explain). The first two-thirds of the story follow a now classic narrative thread, oscillating between moments of hope (the loving family, the father who softens after a very harsh stance, hope of a way out of the crisis, love and understanding that naturally re-establishes itself) and moments of crisis (rebellion, tension, radicalization of comments and stances, breaking point, etc.). However, the narrative is pleasantly fluid, with new issues emerging (the brother, the relationship between brothers, the common pain that unites the family and partly excuses what is presented as the young man’s trouble), and we appreciate the acting and direction, especially the fact that Vincent Lindon is ordinarized vis-à-vis these social hero roles, presented first and foremost as a victim, as a man trying to do the right thing but no longer sure how to go about it, hoping that things will improve on their own (a form of renunciation in the face of a battle he deems lost in advance). But in addition to the predictability that the narrative introduces for a viewer who no longer allows himself to be surprised by it, we come to regret the approach taken, in particular a form of simplism and shortcuts that seem to us to run counter to the seriousness of the subject (though presented throughout as major). For example, it’s easy to get carried away when the radicalization of ideas seems to come partly from the outside, from acquaintances judged to be bad, and described as essentially masculinist in sporting circles (soccer ultras, militant revolutionary groups ready to smash “unclean” foreigners, MMA fanatics), or encouraged by the jealousy and lack of prospects of those who don’t belong to the elite, and the pedantic nature of those who continue to denigrate extreme right-wing ideas in order to fight against them. At this level, the social study that explains the rise of extreme right-wing ideas (antifas will also be perceived a little later as an equivalent evil…) doesn’t seem to us to go very far, which would have been necessary to intellectualize the film further and make it more necessary… (In the same vein, we much preferred Lucas Belvaux’s Chez nous). If the film won a place in competition at the Venice Film Festival, and if we doubt that it will convince the greatest number of people in a country that has already gone over to the other side – without public opinion crying out, for the moment, at the great deprivation of freedom – it probably owes this to the turn it takes in its finale, surprising both narratively and formally. Speeches suddenly give way to silences and expressive glances, and there’s no time for explanations, after the tragedy has intruded with a radicality we wouldn’t have dared suspect (the latter seems to us personally to be more in line with the warning message conveyed). It affects the whole family, and raises an even greater question of conscience, to which the viewer finds himself invited. A gripping finale, which finally brings us back to the question that the film’s title poses too abruptly and Manicheanly: if we play with fire, aren’t we all going to get burned by it?

Be First to Comment