Last updated on September 4, 2024

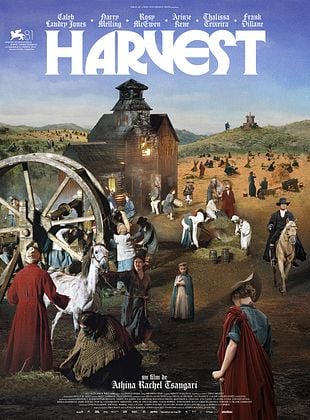

A film by Athina Rachel Tsangari

With: Caleb Landry Jones, Harry Melling, Frank Dillane, Rosy McEwen, Arinzé Kene, Stephen McMillan, Thalissa Teixeira, Mitchell Robertson

Follows the villager’s reaction to three newcomers, who become scapegoats in a time of economic turmoil.

Our rate: ** (but worth seeing again)

As was the case for many viewers, we were taken aback by the film’s complexity, and our review reflects this. We’re giving you a review here, which we’ll be happy to revisit at a later date on a second viewing of the film.

From the very first images, Greek director Athiná-Rachél Tsangári establishes a clear, unmistakable artistic line, a world that lends itself perfectly to painting, a geographical and historical setting, and inhabitants united by a community. But very quickly, what might have seemed established – the era, the borders, the characters’ identities, the relationships that unite them – are radically blurred, to the point of losing bearings and certainties. The language used, which ranges from the modern (numerous “fucks” with a totally assumed anachronism – we even see this as a real intention of the film) to the more ancient, multiplying rare terms, contributes to this general blurring, which is not further clarified by the events, which are difficult to read, and generate chain reactions obeying a logic that escapes simple interpretation (cause, consequence). Rationality most often gives way to emotion and impulse, and the collective or collectives are driven by rather secret and sometimes contradictory ambitions (fear of the other, foreign or different, trust in the other, in goodness, attraction coupled with repulsion, archaism, fear of fate, of the devil, fear of desire or of becoming attached to the other…). …) This world we are given to see survives, unknowingly living out its final hours, and, as we shall learn later, in a great illusion. It then occurs to us that Harvest, whose political component (racism, feminism, political games, hypocrisy, appearance, clans, struggle for influence, seduction of the population… ), whereas a Mallick would have focused on the religious and mystical, telling us about an era that is much closer to us than it seems, where a few delude themselves, try to resist modernity and protect their way of life, but an era destined to disappear, swept away by the siren call of capitalism, which has no use for utopian resistance. This concept of telling us about a fictitious community in a remote time would have been fascinating if the intentions had been clearer, or on the contrary, more evanescent, the overall narrative chaos only really allowing itself to be deciphered in small moments. Thus, we come to understand the place of the community’s main characters rather late in the game, assuming a strong friendship (love?) relationship between the leader and his assistant, and we also assume that past tragedies have ravaged the community, with many seeming to have lost their spouses in the struggle. We’ll also learn about the relationship between the assistant, a botanist in his spare time and even a pharmacologist, who records his notes and illustrations in a notebook, and this strange character, a visiting geographer who maps/paints the region. Art and science thus find their representatives, who naturally understand each other. But questions remain as to how we look at politics and political behavior, loyalty, omerta, the real ambitions of our characters, their loves – extinguished or thwarted, their desires, their reversals of behavior towards each other, but also the events themselves that resulted in the implosion of the community, when it seemed, outwardly, inexorable anyway. Frustratingly, this very dark tale, with its complexity and unconventional plot, did not reveal all its secrets…

Be First to Comment