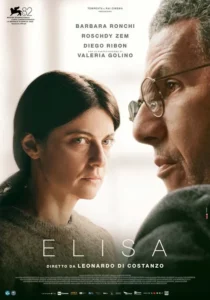

A film by Guillermo del Toro

With: Oscar Isaac, Jacob Elordi, Mia Goth, Christoph Waltz, Felix Kammerer, David Bradley, Lars Mikkelsen, Christian Convery, Charles Dance, Burn Gorman

Dr. Victor Frankenstein, a brilliant but egotistical scientist, brings a creature to life in a monstrous experiment that ultimately leads to the undoing of both the creator and his tragic creation.

Our rate: **

When we indulge in the somewhat reprehensible practice of rating films, we usually count the points we liked about a film, those we liked less, and try to justify our rating. The negative points may not have put us off the film that much, and the positive points may not have amazed us either, but simply held our attention. Sometimes, films simply seem good to us, or not so good, without any particular highlights, so we judge them as a whole, from the staging to the narration, from the aesthetics to the acting, including technical criteria and emotional responses. A comedy that made us laugh will be rated higher than a horror film that didn’t scare us, for example. But rare are the films that leave us with a double impression, ambivalent and contradictory, that of a film that is magnificent in many ways, but in many others a total failure. Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein (which we don’t particularly hold dear to our hearts, readily classifying him as a mere craftsman) falls precisely into this category. It did not leave us indifferent, far from it, and it inspires our pen as it stimulated our neurological receptors… In a nutshell, it is both distressing and wonderful at the same time! The Golden Lion may be within its grasp (but at the time of writing, we already feel that Ann Lee’s Testament deserves it more), but its success on Netflix and in theaters is absolutely certain. We are, of course, dealing with a major work, a perfectly executed mechanism, perfectly designed to provoke sensations (surprisingly few in the horror genre, to which the film nevertheless belongs) and so laughable… Great music, as our grandmothers would say, the kind you want to turn down urgently because it is so unbearable to those who appreciate chamber music… Great art… literary art at that… in this reworked Frankenstein, all the monsters lie dormant: those of Victor Hugo (the hunchback of Notre Dame), Stoker’s (Dracula), King Kong, Terminator, Moby Dick, the beast from Beauty and the Beast, Steinbeck’s (Lenny in Of Mice and Men) evoked more or less directly, like the mouse on Frankenstein’s shoulder, or the sunken ship… All the myths are brought together in a single creature, surpassing Mary Shelley’s writing and previous film adaptations by J. Searle Dawley, James Whale, and Kenneth Brannagh, but similar to the attempts of filmmakers such as Jesus Franco and Ishiro Honda, who were the first to devote themselves to this kind of mashup… Del Toro therefore pulls out all the stops, basing and structuring his narrative on a basic grammar where each character plays their part, each group has its predetermined raison d’être, carefully thought out in the writing, within a rigid framework, that of a totally controlled machine, which nevertheless fundamentally escapes its creator, who completely misses the point: the raison d’être, the reason for the action. The heart. Del Toro, a demiurge in the guise of Victor Frankenstein, thus pushes forward, with obvious success, the reflection on what the monster reflects of man at his extreme. The constant confrontation between ugliness and beauty (even in the sets and other special effects), cruelty and kindness of soul questions one thing and one thing only: Man. Overpowering, and sorely lacking in finesse and subtlety, to the point of becoming laughable in a second part where the narrative structure is reversed, Del Toro follows in the footsteps of Kurosawa (Rashomon) (and before that, Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, Mary Shelley’s original work, which presents this story within a story), seeking, after the terrifying tale of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, to move us with the more sensitive story of the creature, who endured from his creator the same suffering that he himself had endured from his father (two-bit psychology).

This Frankenstein may, even more than many films, bring us back to the great debate about the very function of cinema, about the auteur’s gesture in contradiction with the industrial gesture or serial writing by several people.

Almost every critic has seen their cinematic journey take detours. Very often, entertainment cinema accompanied their first cinematic desires at a young age. From Return of the Jedi to La Maman et la Putain, for example, the only common denominator is the (almost religious) fascination that both films exerted at different ages. Eyes full of stars, minds full of thoughts. From the search for thrills, the need to be transported into a fantasy world, to encountering a work that perfectly mirrors one’s conception of the world and life, to the need to satisfy an insatiable curiosity, to learn and travel inwardly, a journey from which one emerges grown, not numb.

Here, with Frankenstein, Del Toro and his team feed our nightmares but also, for our inner child, our longing for fairy tales. Nightmares forbidden to those under 12, but probably, alas, a tale forbidden to those over 16, due to its overall incoherence, its narrative excess without limit or safety net, its sonic exaggerations, and its particularly ridiculous action and love scenes, as predictable as they are useless or seemingly out of nowhere.

Be First to Comment