The animated film White Plastic Sky, directed by Sarolta Szabó and Tibor Bánóczki, made quite a splash when it premiered at the opening of the Festival National du Film d’Animation. White Plastic Sky has been acclaimed wherever it has been shown. It should appeal to a wide audience, offering a credible alternative for science-fiction fans to the best of the genre (there’s not only Dune . ..). Above all, the film has the singularity of displaying very high ambitions on every level, from the script, through the animation technique, the image, but also and above all the direction, which is highly inspired and inspiring.

A film by Tibor Bánóczki ,Sarolta Szabó

With: Zsófia Szamosi, Tamás Keresztes, Géza D. Hegedűs, Judit Schell, István Znamenák, Zsolt Nagy, Márton Patkós, Olasz Renátó

2123. Faced with diminishing resources, the human race can only survive through a trade-off: at the age of 50, every citizen is gradually turned into a tree. When Stefan discovers that his beloved wife Nora has voluntarily signed up for donating her own body before her time, he sets out on an adventurous journey to save her at all costs.

Sarolta Szabó and Tibor Bánóczki were kind enough to answer our questions, and share with you some of their secrets and intentions.

This is your first feature film … With no shortage of ambition … Were you aware of this on the day you said to yourself, “Let’s go for it, this is the film we’re going to make”?

Around 2014 – 2015 we felt that after our short films, we reached the moment when we were ready to use all our knowledge and energy to start a feature film, which was always a shared dream of us. At that time, we developed different feature film ideas on topics that interested us. The idea of White Plastic Sky crystallised in 2015 and we actually jumped headfirst into the challenge. It was a now or never moment for us.

You are both credited as Writer, Director, in charge of shooting and Story Boarding. How did you divide up the roles, and how do the 2 of you work together? Is it always easy between you?

We did several short films and music videos together before we started this project. Of course, making a feature was a completely different world. We had to work with a bigger and more complex story, we could work with a bigger crew, we had live action shooting and working in co-production with a different country also brought new challenges. The complexity of the work and the pressure increased significantly and these new experiences acted as a catalyst for us.

We always share the work in all areas – writing, directing, concept design, cinematography – and we believe that continuous dialogues, brainstormings and immediate feedbacks on all thoughts can produce good results in team work. Of course, we don’t agree on a lot of things on a daily basis, but during the communication we always try to keep in mind that discussion can’t just become a battle of egos. We trust and respect each other knowledge, taste and talent. The point is that those ideas that serve best to improve the project get the green light.

The film follows in the tradition of Hungarian animation, which is doing well, with 27 winning the Palme d’Or for short films last year. Was it important for you to make your first feature film in Hungary?

It is very difficult to start an animated feature film, especially when directors want to make their first film. While in the live-action film environment it is natural for directors to make a feature film after a few short films, in animation this is not such an obvious career path – many people work exclusively on short films or/and series throughout their career.

In general, directors always make their first feature films in their native country, which is understandable, since it’s in the interest of every country to nurture its talents. At the time when we started this film in Hungary, the support of Hungarian animated films at home was not ideal (unfortunately, the situation has not improved since then), but there was a competition for first time filmmakers – the Incubator program of the National Film Institute Hungary (NFI) – , where we won a minimal budget for the project. After that, we got a Slovak producer and Slovak Film Fund involved, and since the NFI saw more potential in the film, we were able to apply for additional support in Hungary. As a Hungarian-Slovak co-production, we then successfully applied for support at Eurimage. In this way, we managed to increase our budget to 2 million Euros – during production – , which was an unusual situation, since for a long time we did not know exactly what the final budget would be, but the film was already in the making.

Your story takes place in Budapest. Just as the Americans have been able to do (without asking too many questions) with New York or Los Angeles on numerous occasions. Was it important for you to situate your story geographically, rather than aiming for a form of universalism?

Although at the very beginning of the development we imagined that the film would take place somewhere on Earth in an unspecified country, it soon became clear that this was not a good approach for this story. Using the animation medium could be limitless designing a futuristic city, but we did not want to create a very sci-fi look as we thought it would go against our love story. The human relationship is the heart of the story, the design has to built around that not the other way around. A heavy sci-fi design would disorient and divert the focus from our characters.

It was on the basis of these thoughts that we came to realize that we had to choose Hungary and Slovakia as locations, the places we know very well. The destruction of our country has brought many resonance with our current political issues. In our film Budapest isolates itself from the rest of the world. We can see this in our current foreign policy. So we can say a dome can be built over a country invisibly. We also thought a lot what could happen if our government announce the 50 years life span? Would us Hungarians go onto the streets to demonstrate or just accept it silently?

You worked on short films in France before moving to Hungary to direct this feature. What did the French animation school bring you? And, more generally, your apprenticeship in Europe?

After graduating in Hungary we had a strong desire to explore the world – we wanted to study, work and live abroad. So we moved to London in 2005, where we both completed a course, Sarolta at the Royal College of Art in Fine Art Photography, and Tibor at the National Film School in Animaton Direction. During this time we started our artistic partnership focusing mainly on animation projects.

We moved from London to France when we won the opportunity to make a short film at Folimage Studio and “Les Conquérants” was born, and then we made the film “Leftover” with Paprika Films and Ciclic.

These years were very important because we built a lot of professional relationships with people with whom we have worked together many times since then. In France we got to know the professional studio environment and gained a lot of experience making short films, which was our basis when we ventured into the feature film. In addition, of course, many friendships were born, which we have cherished ever since.

We’ve been familiar with the Hungarian school of animation since the 80s, notably René Laloux and “Les Maîtres du temps” … Was it one of the films that inspired you?

This movie was a defining childhood movie experience for both of us! We were around eight/ten years old when we saw “Les Maîtres du temps” for the first time, which in retrospect was quite a serious and unexpected film. Back then, they didn’t really care about age ratings in movies, so we loved and dreaded every moment of it when we watched in the cinema and read the comic based on the movie at least once a month. Looking back, it may be surprising that it was shown at all in Hungary, which was behind the Iron Curtain at the time (the animation works of the film were made at the Pannónia Film Studio in Budapest), since the message of the film was in strong conflict with the Hungarian political system at the time. “Abolish the unity of uniformity!” It is no wonder that the regime change in Hungary took place soon…

Generally speaking, do you share any inspirational references in your intentions, be they graphic/pictorial, artistic, literary, and why not on the side of science fiction writings or films?

The theme of metamorphosis – existence between different lifeforms – is as ancient motive which appeared in different cultures and art forms. From Ovid’s Metamorphoses through the mythological tales of Philemon and Baucis to the Seventh circle of Dante’s Hell. Many stories, characters and visual art works have influenced us during the development process.

Hybrids of plants and humans are the most poetic and intriguing ones. Could humanity understand another kind of life? Plant life seems much more secret, hidden with seemingly more unknown factors than animal life and although there are more and more studies how trees and plants feel and communicate, it is still a mystery. We look with constant awe at the majestic tranquility of the trees, we admire their seemingly eternal existence, since some of them began their earthly life more than 5,000 years ago, so they are older than any ancient human civilisation. This kind of live is still almost unimaginable for us humans.

High concept science-fiction films always refer or rather forecast problems and crisis of the world and undeniably share some common motives what directors wants to unwrap from time to time. Although films like Soylent Green or Logan’s Run deal have some similar motives as White Plastic Sky, the problem of food producing, ageing, etc., the core concept and the centre questions are different in each of this films.

Your story interweaves hope and despair, dystopia and romance. It’s both an end-of-the-world tale like those written by Abel Ferrara (4:44 Last Day on Earth), David Mackenzie (Perfect Sense), Lars Von Trier (Melancholia) and others, and a dystopian tale that questions the end of life and the transformation of the human body and soul (reminiscent of the obsessions of Lanthimos (Lobster)) in a futuristic world that amplifies the failings of our times (reminiscent of the look of Jessica Haussner (Little Joe)). Last but not least, we find a recurring theme in many science fiction films, where a hero crosses a mirror or interstellar space to enter a parallel, virtual world that resonates with today’s world, and embarks on a quest to save his beloved, or indeed the whole of humanity.

Where would you say your story comes from, and how did you go about balancing it?

It was a fundamental cornerstone of our film that we did not want to show the arrival of the final catastrophe on the Earth, but we were curious about what happens AFTER the catastrophe. We wanted to tell about what kind of future awaits a tiny society of survivors on a dead planet after humanity disappears with the complete extinction of flora and fauna.

It was important to us that our heroes be everyday vulnerable people, not fearless superhumans. Our protagonists are a married couple whose relationship is in crisis and they discover the outside world while rebuilding their love. The story is built on the fabric of human relationships and consists of a series of encounters – with lovers, wives and husbands, mothers and fathers and their children – through whose choices and decisions this world is mapped.

Beside philosophical questions the poetry in metamorphosis offered a great motive for love. Through the long lifespan of trees we could offer our main characters something they wouldn’t be able to live as human beings: seemingly endless love. It was important for us to examine this idea and to think about the possibility that other life forms are capable of this emotion too.

The dystopian set in White Plastic Sky is a disturbing decoration, but what we really wanted to discover is the paradox of sacrifice. Whether humanity is able to choose between the bigger issues and between family and love matters. Is it possible to sacrifice ourselves, our children, our love to the greater good? Or is it an illusion only?

It was clear for us from the very beginning of the development that we want to give an uncomfortable ending for the audience. We wanted to show very different choices in this dystopian world. They can sympathize or they can reject the characters’ solutions and answers. Is it the right decision what our main couple do at the end of our film? Maybe yes, maybe no. But this is the choice which can stimulate us to think further what can or should we do on this Planet. In the uncertain world we live in today, as filmmakers we felt that we should not force any answer on anyone. That is the job the audience has to do.

One of the pleasures of both animation and science fiction is the ability to compose an “imaginary” world. How did you build it? Parcel by parcel, or more as a whole, with precise constraints that you set yourself.

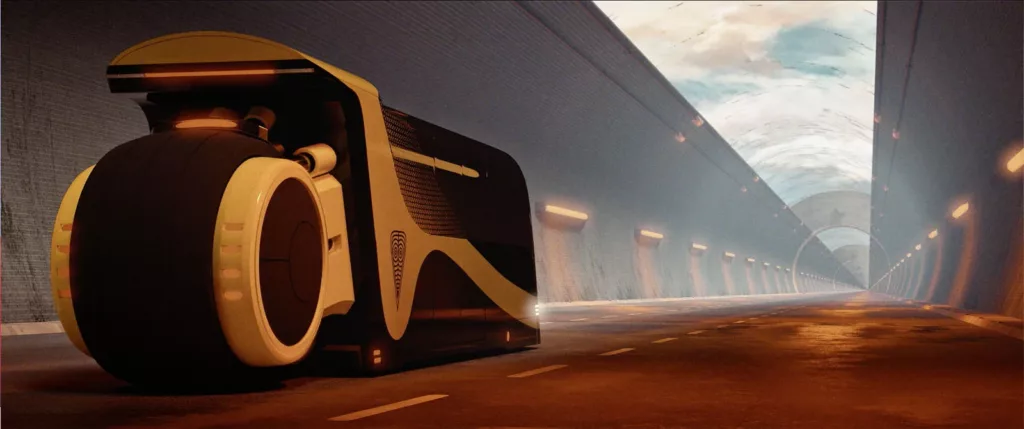

Since we had to do as many tasks as possible in the film due to the tight budget, we were also responsible for concept art and design. It was a guilty pleasure to destroy and transform everything in the remains of a post-apocalyptic Budapest and Hungary. We carefully considered everything, what was left of the world as a result of the changed climate, what the landscapes and buildings look like as a result, how they changed and destroyed in 100 years. There was a question about how the city of Budapest will be rebuilt under the dome, and how the materials of the abandoned buildings and the desert sand from the outside world will be used for this purpose.

Although we tried to create an architectural environment close to today’s Hungary, it was important to create exciting places and locations, such as the Plantation under Lake Balaton or the Granum research center in the Tatra Mountains. We created sketches, blueprints and descriptions for every landscape, building, object, machine and vehicle, which were then built by our Hungarian 3D modelling team and we refined the details together with them.

Science fiction and animation go particularly well together. Animation allows us to go even further into the imaginary than the 3D techniques employed by American studios. Take Dune, for example, we see a film set in the desert, not in a universe that is completely foreign to us. Was it important for you to push the imagination as far as possible? But also, on the other hand, that the rotoscopy (the real shots) fit in perfectly with the drawings?

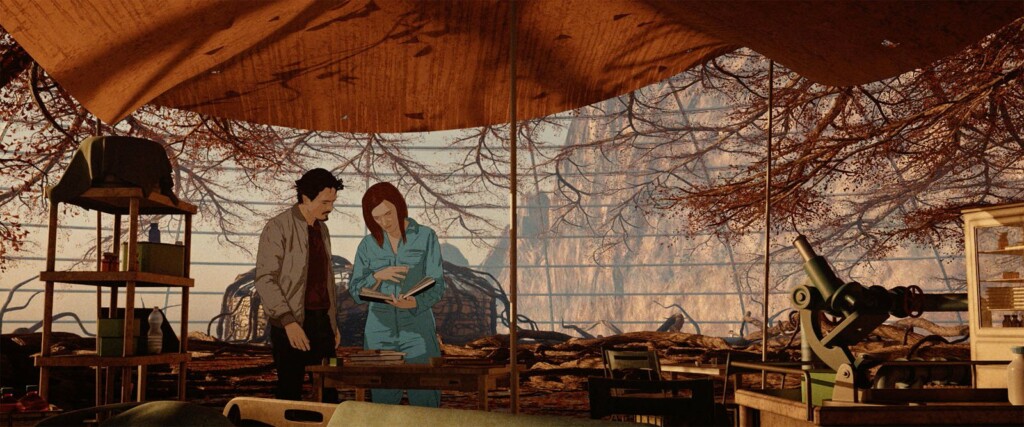

It would never be possible for us to make this story a live action sci-fi film with the circumstances we were working in. Although White Plastic Sky is an extremely low budget film, we could imagine and managed to create any scenes we wanted. From the very beginning we knew that this story and this genre needs a certain production quality to reach its audience and although we worked with a small crew, with a lot of work and enthusiasm we managed to produce a high production value. Using a mixed animation technique and rotoscope felt a good match for the film’s theme conceptually. Exploring different life forms White Plastic Sky is also a hybrid itself, existing between animation and live action films.

Graphically or plastically speaking, it must have taken a lot of time to build the sets… Can you tell us about the way you work with your teams to ensure that the results correspond to your initial idea? Did you give them a lot of freedom, or were you more concerned with precise orders and control?

We were in constant communication with the Slovak and Hungarian 3D teams, who worked on the texturing and colouring of the 3D environment, special effects and animation of the vehicles. We gave daily feedback to all team members who worked on the scenes and the animators as well. This is a very meticulous and lengthy part of the animation directors’ work, where they have to pay attention to every little details.

Finally, the character animations were added and the scenes were finally assembled and fine-tuned with the compositor colleagues. It was a magical process, as starting from the script and the first sketches, each scene was slowly born during a long evolution through the work of our team.

You chose to use rotoscoping and well-known Hungarian actors, whom you filmed in live action. Can you tell us about these choices, and the advantages and disadvantages they brought?

We handled the casting and the shooting as a live action film and wanted to achieve a quite naturalistic acting you see in live action films. We did not want any overacting which might be familiar from certain animated acting style. Our characters are not animation figures, they are breathing, living humans with deep and complex emotions.

We had a fantastic cast with the Hungarian actors, who were very open to the unusual challenges coming from the film’s animation technique and they enjoyed the whole process.

The most important and hardest task was to preserve all the subtle details of their acting throughout the rotoscopy process. We did not use any software to help the rotoscopy, all drawings made by the hands of highly skilled animation artists. The sensitiveness of the drawings styles could also emphasise the acting we recorded during the live action shooting.

Can you talk about the directing work itself, but also the writing process, and how this differs from the directing and writing of a live-action feature?

In many ways, this film was very similar to a live-action film in terms of both writing and direction. The essential difference is caused by the techniques we used in the final visuality: an animated film was created by the 2D animation and 3D visual styles.

In the early stages of writing the script, we started working on the animatic in parallel. The animatic is like a storyboard, where we put the scenes together from simple drawings, but it can be played like a movie. It helps us already in this phase to experiment with film language, editing, cinematography, and rhythm, which affects and helps the writing of the script. The storyboard required for the live-action filming was then put together and we worked with the actors based on it.

For a traditional film, you certainly don’t want to waste any film stock, but for an animated film, it’s almost forbidden to have to throw away images that have already been shot, if you want to stay within budget… So you have to go through a storyboard and other stages that set a very strong framework for the film. And if you come up with other ideas for staging, camera placement or sequences, it must be very complicated to get the team to accept them. Yet these new ideas, these arrangements with the initial script, can be necessary when the film starts to be viewed as a whole and you test it… Can you tell us about how this happened with White Plastic Sky?

Of course, it always happens that problems arise that are more difficult to solve or that certain things have to be tried in several ways. Due to the small budget and small team, we had to work very consciously and make careful decisions in order to create as little unnecessary work as possible. Every animation should be accompanied by a great editor. We worked with Judit Czakó from the beginning and we experimented a lot with editing already in the animaticphase. It happened that some parts of scenes that had already been completed had to be cut, but the amount of these was of course negligible compared to live-action films.

Since the backgrounds were made in 3D, we were able to modify the camera settings during later work phases, just as the editing also gave us room for minor changes at a later stage.

Since the animation was based on this live-action material using rotoscope, during the further work we were able to change the placing of the actors in the scenes, since the backgrounds were made separately in 3D for the scenes, which gave us some freedom.

At what stage in the writing process does music come into your way of working?

We have been working with Christopher White for 15 years now. (he was a fellow composer student of Tibor at the NFTS). Christopher has been working with us on all our short animations before and there was no question we wanted him on board for White Plastic Sky too.

We always start our collaboration with him on the earliest stages of the animatic. The scores go through many phases as the movie evolves throughout the years. We also try different feelings until we catches the final mood. Christopher understands the length of an animation production perfectly and he is an amazing creative partner.

An animated film exist in a sketch format for a long time, which means scenes are very far from finished and they are changing all the time. You see the colourless layout backgrounds and unanimated scenes for years and as a composer you have to imagine them beforehand and write a score for them. For this you need a lot of imagination and a great sense of visuality.

Most of the time, we approached the music from the emotional side, we have talked a lot about what is the purpose of the scene, what happens with the characters emotionally, and what the audience should feel when they watch the finished scene.

The overall rhythm you build up is rather contemplative (as Laloux liked it, but also the Japanese animation masters (Galaxy Express, Albator, …), which helps establish a mystery, an atmosphere that suits dystopias perfectly, but for all that, towards the middle of the film, the action kicks in. The characters race against the clock.

Here too, can you tell us about the balance you sought to create?

We are really fond of the so-called Eastern European slow cinema and we thought it is necessary to explore it regarding our dystopian theme even if slow cinema was not born to suit the animation medium. We also wanted to use different rhythms throughout the story. There are some action scenes of course, where the pace accelerates, but also many times we have slowed down the story to let our characters some time to wander and explore. In the dead, desolated world time has lost its meaning, so there is a big shift in terms of pacing when our characters reach this place.

On the technical side, sometimes the characters have to move around in virtual sets, notably climbing trees. We can imagine that these scenes would have required very fine tuning, and possibly the reproduction of drawn sets in real settings.

Fortunately, we had few scenes as complicated as climbing trees. We were shooting in a small photo studio with the actors, where we actually built an object from the furniture and things we found in the studio. On this, the actress was able to move as if she were walking on tree branches. We recorded these scenes in smaller separate pieces and assembled the entire scene during editing, which was then redrawn by the animator. Then, during the 3D modelling, we placed the position of the tree branches to the actress’s movements.

The difficulty isn’t always where you think it is. What was the most difficult thing for you to do on this film?

Sound design was a fundamental issue in this film. We worked with Stefan Smith (also an NFTS graduate) on this project. It was a big task to fill with sounds the planet where all life was silenced, the leaves of trees, birds, cars, and human noises disappeared. Stefan also followed the film from the beginning and started working in the animatic phase, which was very important in helping us to feel the locations, time and rhythm of the film during the work.

It’s been 7 years since you said, “Let’s do it”. Did you imagine that things would turn out the way they have so far?

Our main story was already dystopian enough since the beginning, so actually it was the world which moved closer to our movie. Sarcastically we could call ourselves lucky that our source material did not age throughout the years of the production but one could say that quite sad.

Perhaps the most frightening was how the changing history has filled with other meanings some of the scenes we have created beforehand. For example the children toy tank become some kind of metaphor of the neighbouring war. The toy tank was in our scene long before the Ukrainian war but sadly become more menacing image than we could ever imagined.

Be First to Comment