Last updated on February 24, 2023

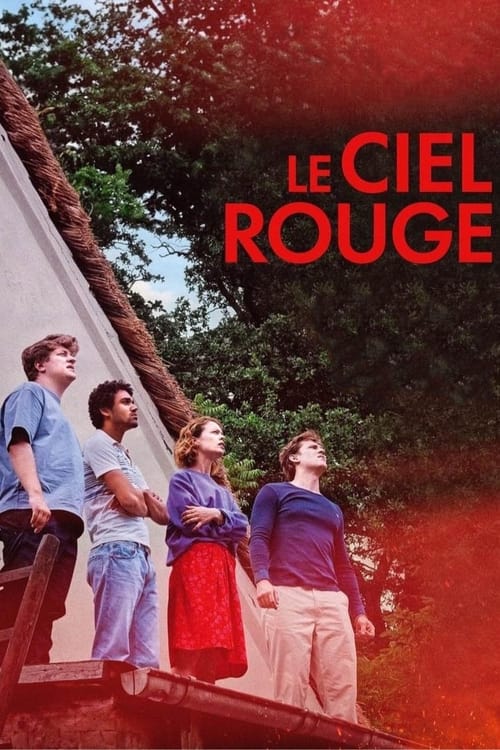

A film by Christian Petzold

With Thomas Schubert, Paula Beer, Langston Uibel, Enno Trebs, Matthias Brandt

Four young people in a holiday home on the Baltic coast. Three are having fun but one – a writer – is struggling. The forest burns, the sky turns red. Petzold’s latest waking dream is a tragicomic relationship drama that shimmers but is also down-to-earth.

Our review: ***(*)

Christian Petzold admits in a press conference that after Ondine, he was in France thinking about a film that could be considered for the Cannes Film Festival. He then contracted covid, which left him and his wife bedridden for almost a month, and the idea came to him of a vacation story that was not like the stories that German cinema likes to put on the screen, where the question of coming-out is invited to the family table after returning from a sunny period of discovery and emancipation. He is thus surprised that France offers its own style of summer stories (he does not cite Rohmer or Téchiné) as well as that American cinema also offers a sub-genre. He then set himself the challenge of constructing a story that escaped the usual codes, and found his inspiration in the forest fires that raged shortly after in Portugal. Above all, beyond the multiple staging – the film does not necessarily deliver linear intentions, intertwining romance, drama, danger, all with an apparent lightness reigning – Petzold finds his subject at the same time he finds his main character. His psychology, his propensity to see the world from an egocentric angle, to be blind to what is happening around him, constitutes the very material that the film kneads. In this, Petzold follows the path of Rohmer, who likes to theorize and ask existential questions about the different forms that love, emotion and its impulsive counterpart, desire, can take, but he also follows the line of Téchiné, who likes the facts to build the characters, to catch them in their own way of thinking, and to surprise them. The strength of Ciel Rouge lies on the one hand in its ability to project us “In the mind” of its main character – the film opens with the heady music In my mind – but also to offer us an outside view, amusing at times, more thoughtful and serious at others. Petzold questions success, talent, inspiration (using literature in general, and the title of the fictional work Club Sandwich to better evoke Petzold’s cinema, and his film Cuba Libre), self-criticism, condescension, contempt, jealousy, anxieties, paranoia, erotomania, social labels, power relationships, humility, empathy, innate talent and false appearances, sexuality and its relationship to it, but also the relationship to success, seduction as a weapon or source of success. Inspiration, precisely, he tells us in this story, must come from experience, from digested experience, and not from the pretentious exercise of fabrication that relies only on emptiness. In addition to its thematic richness, the finesse with which Petzold manages to suggest things and to make inner thoughts visible on the outside, Afire has a very beautiful quality of rhythm, precisely because its form evolves as the story progresses

Be First to Comment