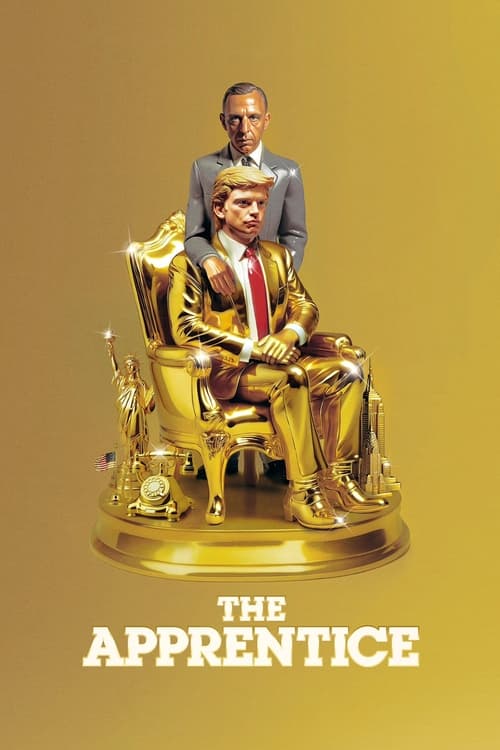

A young Donald Trump, eager to make his name as a hungry scion of a wealthy family in 1970s New York, comes under the spell of Roy Cohn, the cutthroat attorney who would help create the Donald Trump we know today. Cohn sees in Trump the perfect protégé—someone with raw ambition, a hunger for success, and a willingness to do whatever it takes to win.

Ali Abassi was back at the Cannes Film Festival (after Border and Massad’s Nights, two films that won him awards and international recognition – respectively Prix un Certain Regard and Best Actor for Zar Amir Ebrahimi), with a proposal that was the talk of the town even before it was discovered. It’s probably no coincidence that the film was released in France just a few weeks before the American election, which is due to deliver its verdict on Tuesday November 5. The young Iranian director tackles a quasi-myth, a businessman who fears nothing, not even shame. Our age openly exposes the diversity of opinions, giving less room to the intelligentsia, to the control of opinion, not sparing of ambivalence: speech is liberated, access to culture and intellectual material facilitated, when it was once reserved for an elite, information more easily verified and contradicted, in a flow of images once non-existent or in the hands of a few powerful people, battles are being waged against behaviors that have gone on all too long, galvanizing essential struggles (ecology, feminism, egalitarianism, pacifism, . …), but for all that, we can only observe an influx of false information, massive disinformation campaigns, a levelling down, a conservative reflex which allows statements that were thought to belong to an ancient century and long fought against, not only to regain ground, but also to be heard.

Preceded by a reputation as an anti-Trump pamphlet, The Apprentice was supposed to adopt a radical form, to support its message with force and persuasion, to shed light on the darker side of the character, and even to reveal scandals, while finding a form and an aesthetic that would justify its presence in the official competition at Cannes. An exceptional background, an exceptional form. But even before discovering the film, our minds had been led astray by this false trail (the film is not lacking in them): surprisingly, Ali Abassi proposes a completely different path, with confounding boldness.

His portrait of Trump, far from being vitriolic about a caricatured personality, is reminiscent of initiatives such as The Social Network. In terms of form, we recognize the grain of the new Hollywood, when New York glowed in the night and was filmed on film. Constructing his narrative entirely like a success story, Ali Abassi sets about putting it into images (eigthyscape, zooms, dezooms, in constant motion), music (essentially New Wave), and words (there are few silences, few deep thoughts, more frequent little phrases testifying sometimes to naive thinking, sometimes to a deeply ingrained ideology). The choice is yours: we can see it as a good film, thanks to a style a little out of fashion, or as a Dallas electrified to the point of seeming deeper than it is, entertaining as it needs to, but also continuing to nurture the American Dream while underlining a few conservatisms with a touch of humor sprinkled here and there.

Nonetheless, a Sidney Lumet (or even a Scorcese, a Coppola, a Fincher more surely, to name a few immediate approximations) would probably only have set out to explain the character’s wicked twist – when the pupil surpasses the master, but beware here without rebellion, Trump is no Darth Vader, let’s be clear, Abassi tells us! – by the fall of the weaker brother, who maintains Donald’s “walk or die” attitude. Nor would he have recounted the story’s two significant descents into hell, that of the brother, Freddy Trump, who disappoints his parents by being nothing more than an airplane pilot, feeding destructive demons – where Trump stands tall – or that of the lawyer – the beloved trainer – in such an accelerated fashion!

The Apprentice does, however, leave its mark. This first-degree narrative calls on viewers to question what they are seeing: a critique of Trump, a tribute to the American Dream, a well-executed, electrifying piece of entertainment, a trompe l’oeil – and a trompe l’esprit? One symbol carries this questioning more than another, the borrowing from Schubert, and in extenso from Kubrick, foreshadowing that Trump, after a victorious life due to his “resilient” and willful character, could sink like Barry Lyndon sank, through pride and vanity.

Cinematographically, if we detach ourselves from the background, Abassi’ s The Apprentice is indeed an object that resolutely refers us to American cinema, to the American industry as much as to its independent fringe (Scorcese as well as Coppola can easily fall into both categories, ultimately, not very orthogonal). In this film, he demonstrates the qualities already seen in Night in Mashad: electrifying direction, meticulous photography and excellent acting. We were thinking of an acting prize at Cannes for Sebastian Stan, much more interesting here than in A Different Man (which we suffered through at the last Berlinale). Perhaps an Oscar awaits him, as Hollywood likes its performers to dress up as monsters (sic). Another Oscar, for supporting actor, would also legitimately go to Jeremy Strong, so apt are his two roles (the strong man, then the weakened man).

Be First to Comment